Austria's GP Ice Race delivers chills and spills

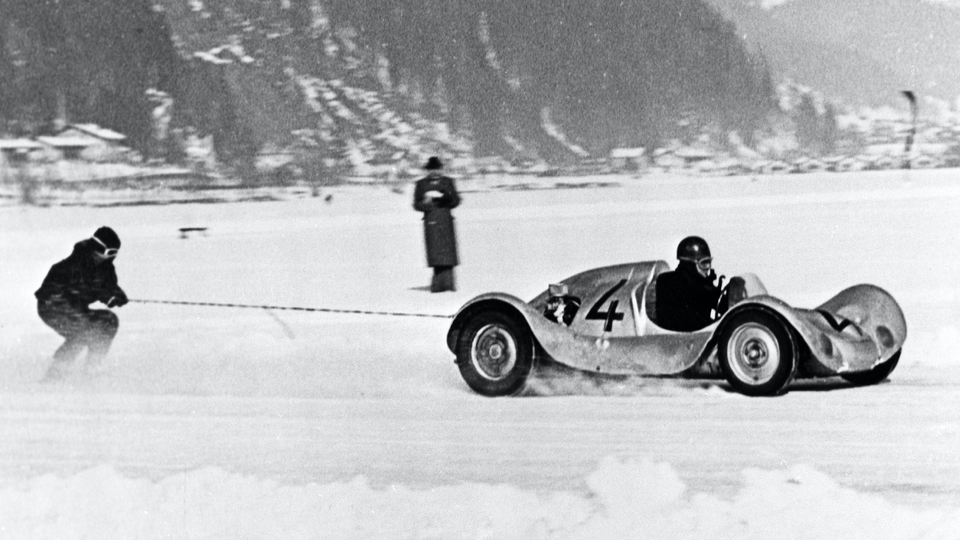

The heir to the Porsche empire revives a risky auto race on the icy Austrian Alps.

On an airstrip in the shadows of the Kitzsteinhorn glacier in the Austrian Alps, Ferdinand Porsche watches as some of the world’s fastest cars whiz by on ice at almost 90 miles an hour, spraying spectators with snow during sharp turns.

For the second year running, the 26-year-old son of the Porsche supervisory board chairman and a scion of Austria’s wealthiest family has overseen the revival of a decades-old tradition of sports-car races on ice.

Over the weekend, he and a friend, Vinzenz Greger, 30, brought together world-class drivers like Rene Rast and Daniel Abt for a race in near-zero temperatures before 16,000 car-crazy spectators with Queen and Jonas Brothers tunes blaring in the background.

This year’s GP Ice Race, though, was not like those between 1937 and 1974, which took place on the frozen Lake Zell. With the lake now failing to freeze over, it was held on an airstrip iced over with a tractor and a water-tank.

For Ferdinand, restoring the race in an era of climate worries is about rekindling a family passion for testing the boundaries of well-engineered machines against the elements while also trying to be responsible by keeping laps short and limited and driving cleaner cars.

Racing on ice

“I know it’s a bit crazy to start a car race when everybody is talking about the climate,” he said in an interview, standing in front of the airstrip in a bright blue overall and yellow mountain shoes.

“But we’re actually trying to get motor-sport into the 21st century by having classic cars and totally new ones that are running on low or zero emissions.”

For the first time, the race’s emissions are being balanced out with green actions that will reduce 144 tonnes of CO2.

While the race had cars from the 1950s, 60s and 70s, it also featured an increasing number of electric vehicles from the Porsche and Volkswagen empire – from the Audi Formula E and the Volkswagen ID. R to the Taycan Turbo S.

In the end, rally models of Skoda, Mitsubishi and Ford took first, second and third places in the race. The new, street version of the US$185,000 electric Taycan was Porsche’s top finisher at 23rd in what was its first such competition.

Greening is a relatively new phenomenon for car races, which burn large amounts of fossil fuels and have a notoriously bad environmental record. Formula One has pledged to become carbon neutral by 2030, while Indy race cars now run on 100% ethanol fuel, a corn-based, renewable energy.

For sports-car aficionados in attendance at the Alpine ice race, the green wave and the fact that the event was being held on a track near the lake rather than on the lake itself did little to dampen spirits.

“Car racing is pure emotion,” said Bastian Nusser, a 22-year-old engineer, eyeing a Volkswagen ID. R race car. “It’s incredibly cool that e-cars are now speeding up faster than combustion engines.”

The race had a folksy air, far from the glamour and champagne-fueled parties at Monte Carlo or the ski race next door in Kitzbuehel.

Visitors bought burgers - vegan or organic options at €9.90 were available – and local beers and mulled wine. Guests in a modest lounge were served beef broth and goulash with dumplings, and entertained by a four-man band in traditional costumes playing local folk songs. The race’s prize of honor was a cowbell from a Porsche mountain farm.

While most cars were piloted by men and women in impeccable racing outfits, the Porsche family sported casual clothes, funny hats and colorful jackets and shoes.

The race was held about 60km southwest of Salzburg, in Porsche country. It was there, in Zell am See, that Ferry Porsche bought the Schuettgut farm and estate in 1941 to help feed and shelter his family in war-plagued Austria.

Since 2003, Ferdinand’s father, Wolfgang Porsche, 76, owns the property, spending much of his spare time there.

The third of Wolfgang’s four children, Ferdinand thought of reviving the ice race after he spotted old tires with spikes at the farm’s stable-turned-garage, and his father told him of a time when Porsches raced on Lake Zell.

“Car racing means sweat, team work, long hours, setbacks and achievement – that’s why we do it,” said Wolfgang Porsche, dressed in a dark-blue parka and a white Carrera cap, as he recounted tales of when he was a regular at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, picking up ideas from drivers and engineers. “We’ve learned so much from that for our regular models, it’s the very reason why my relatives got started.”

The race was called off in 1974 because of an accident that killed a worker. That, more unstable weather conditions and additional safety requirements led to the end of the race. The lake needs seven days of below-zero temperatures for an ice layer of at least 20 centimeters, which rarely happens now.

While holding the race again on the lake seems remote and electric cars mean the extreme growl of an engine and the smell of oil and gasoline are missing, the thrill of speeding down an ice track remains undiminished.

"The one reason why I still race is that I’ve always wanted to make sure that I can impose my will on the car, rather than the other way round,” said Hans-Joachim Stuck, a two-time winner of the 24 Hours of Le Mans car race. “And racing on ice is the most difficult thing to do, because you never know what’s next: snow, ice or frozen mud. You need to be alert."

This article is published under license from Bloomberg Media: the original article can be viewed here

Hi Guest, join in the discussion on Austria's GP Ice Race delivers chills and spills