What a 'chronometer' is, and why it matters to the modern watch

You don't have to spend much time around watches before you figure out pretty quick that a chronometer is not a chronograph.

The latter, of course, is basically a combination of a watch and a stopwatch; the former, at least nowadays, is a watch which – assuming it comes from an ISO-standards compliant country, which Switzerland is – has been certified by an independent examination board and found to meet certain minimum standards.

That officiating body today is the (in)famous Controle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres, better known to Watch Idiot Savants the world over simply as the COSC.

Setting the standard

In its current form the COSC has been around since 1973, but prior to that, testing took place at the so-called Bureaux officiels de controle de la marche des montres, which in horological literature are generally more concisely referred to as the BO agencies.

There were different numbers of these at different periods in history; one of the oldest, in Bienne, was founded in 1877. It was these agencies that were responsible for providing independent testing of watches seeking chronometer certification, until they were put under central administration and dubbed the COSC in 1973.

COSC standards for mechanical watches are pretty straightforward. For most watch enthusiasts, the most relevant standard is the one for average daily rate over a 10 day testing period; for a watch to pass, it must maintain an average daily rate of -4/+6 seconds.

Rolex used to get flak now and again for calling its watches "superlative" chronometers on the dials, but in 2015, the Crown introduced the new Day-Date 40, along with a new Superlative Chronometer internal certification, requiring a daily rate of -2/+2 maximum per day. In 2016, Rolex announced it would extend this to all Rolex watches moving forwards.

That's the gist of it for the 20th and 21st centuries. In the 19th century, however, as you go back, you start to see the meaning of the word change as you look further and further back at its usage and evolution.

The chronometer escapement

Below is a key-wound, high-grade pocket watch made by Girard-Perregaux for the English market, dating to about 1860.

One of this watch's technical features is directly relevant to the history of the term "chronometer" (which you can see engraved on the movement dust cover below – with the English rather than French spelling, as this was an English market watch).

That technical feature is the escapement of the watch, which is what's called a detent escapement.

The detent escapement was, as far as we know, invented by French horologist Pierre LeRoy in 1748, although the first practical version of the escapement was the pivoted detent escapement of John Arnold in 1775.

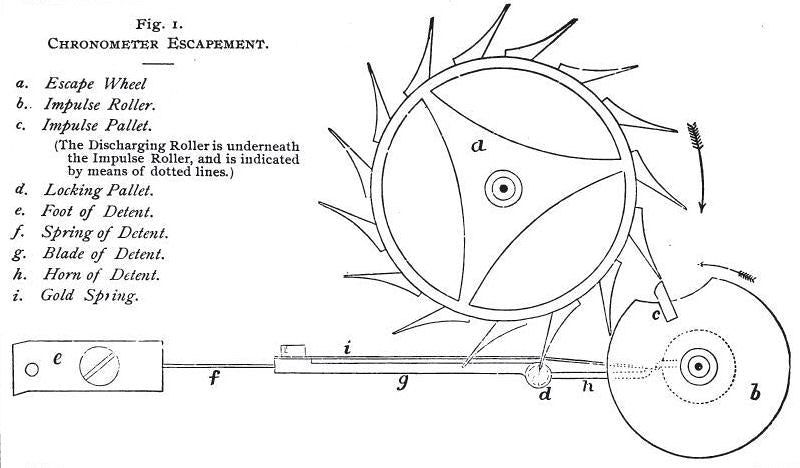

Arnold's contemporary in England, Thomas Earnshaw, was responsible for developing the version of the detent escapement that came to be most widely used, and below you can see the basic layout of the spring detent escapement, as it's shown in the 1896 edition of Britten's Clock and Watchmaker's Handbook.

The way the whole thing works is pretty simple.

The escape wheel is kept from turning by the locking pallet (d) which is maintained in place by the flat spring (f). As the impulse roller (b) which is basically the hub of the balance, turns counterclockwise, a jewel close to its center (unlabeled, in the diagram; it's sometimes called the discharging, or unlocking, pallet) contacts the tip of the gold spring (i) making it press on the slightly shorter horn (h) which shifts the detent aside (downward, in the picture).

This lifts the locking pallet off the escape wheel tooth, allowing the escape wheel to turn clockwise. As it turns, one of its teeth contacts the impulse pallet (c) on the roller, pushing on it and giving impulse to the balance to keep it swinging.

As the impulse pallet disengages with the gold spring, the detent, under the action of the spring (f) flicks back into its original position, just in time for the locking pallet to catch the next escape wheel tooth and re-lock the escape wheel.

On the return swing of the balance, it rotates clockwise; the discharging/unlocking pallet on the balance roller again contacts the tip of the gold spring (i).

However, in this case, it lifts the tip of the gold spring up off the horn of the detent (h) allowing the jewel to pass without moving the detent itself. As the escape wheel doesn't unlock on the return swing of the balance, no impulse is given.

As you can see, for the whole thing to work, the clearances, as well as the tension of all the springs, have to be very carefully controlled. It's a delicate mechanism and takes a lot of skill to make.

The payoff, though, is an extremely precise escapement that's also very efficient. To get a really clear idea how the escapement works I recommend checking out this animation.

The first chronometer watch

The detent escapement came to be called a chronometer escapement, thanks to the use of the word as a designation for a precision watch containing a detent escapement.

The very first person to use the word "chronometer" in reference to a watch with a chronometer escapement, seems to have been none other than John Arnold himself, who coined the term "pocket chronometer" in 1782.

From that point forward, and for some time, "chronometer" primarily denoted (at least, in English language watch and clock-making) a precision timepiece with a detent escapement.

As Fritz von Osterhausen points out, however, in Wristwatch Chronometers, "the main characteristic of a chronometer is its precision," and as lever watches gradually achieved very high precision, the term came to mean, by the 20th century, any very accurate watch.

Osterhausen writes, "In 1925, the Swiss Association for Chronometry defined a chronometer in the following way: 'A chronometer is a watch which has received a certification from an astronomical observatory.'"

Today, almost no one but a few die-hard lovers of antiquated terminology still insist that "chronometer" should only be used to refer to a watch with a detent escapement – which is a good thing for Rolex and Omega and Breitling and a lot of other brands for whom a chronometer rating is a selling point.

Hi Guest, join in the discussion on What a 'chronometer' is, and why it matters to the modern watch