How British Airways created the world’s first business class bed

Lie-flat beds are now taken for granted in business class, but that wasn’t always the case...

The year is 1998. UK Prime Minister Tony Blair is marking his first year of office, while Pierce Brosnan has renewed his license to kill in Tomorrow Never Dies. Apple’s audacious iMac is taking the tech world by storm, although it will be another year until the suited-and-booted brigade clamp eager eyes on the very first BlackBerry and transform it into an executive icon.

And business class is about to take its biggest leap ever, swapping reclining chairs for fully-flat beds.

In the crisp autumn of 1998, British Airways handed London-based design firm Tangerine a brief as broad as it was mind-boggling – to uncover “the Holy Grail of airline travel” and, in the process, totally reinvent business class.

Going flat out to win the business class battle

“BA quite simply asked us to astound them,” reflects Matt Round, Tangerine Chief Creative Officer, who had joined thr firm only two years prior.

“Rather than (giving us) a stack of documents and specifications, they wanted to be really astounded and create a different experience for their passengers."

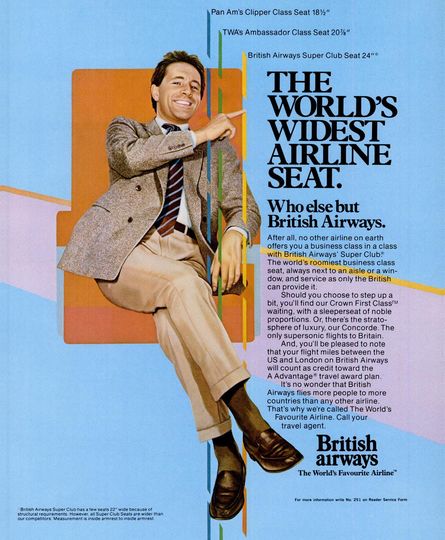

At the time, business class had been steadily evolving from the plush armchairs of BA’s Super Club class (above) to the Club World Cradle (below) – a deep and superbly comfortable recliner which one traveller of the day recalls as “feeling like you were nestled in a giant palm”.

And back in the late 1980s, armchairs were sufficient for the business traveller, as this 1987 advertisement for Club World set out to prove.

But a decade on, even the steepest of recliners wasn’t enough, as Round and his colleagues discovered when they boarded a British Airways Boeing 747 jumbo jet from Heathrow to New York.

“We were looking at the way people were behaving in their seats, what they were doing, their routines,” Round tells Executive Traveller.

“The really critical thing we noticed was flying through different time zones, flying overnight, and needing sleep. And to get a really good sleep you have to be lying down, flat.”

Changing the layout and the rules

However, the notion of fitting lie-flat seats into BA’s business class cabin didn’t arrive as a thunderclap.

“It's not too difficult to put flat beds in a space, that doesn't take much intelligence,” Round admits. “The thing that was important was actually figuring out, how do you get enough people in the space to make it stack up economically?”

Then, as now, the inescapable gravity of economics served as counterweight to lofty ideas.

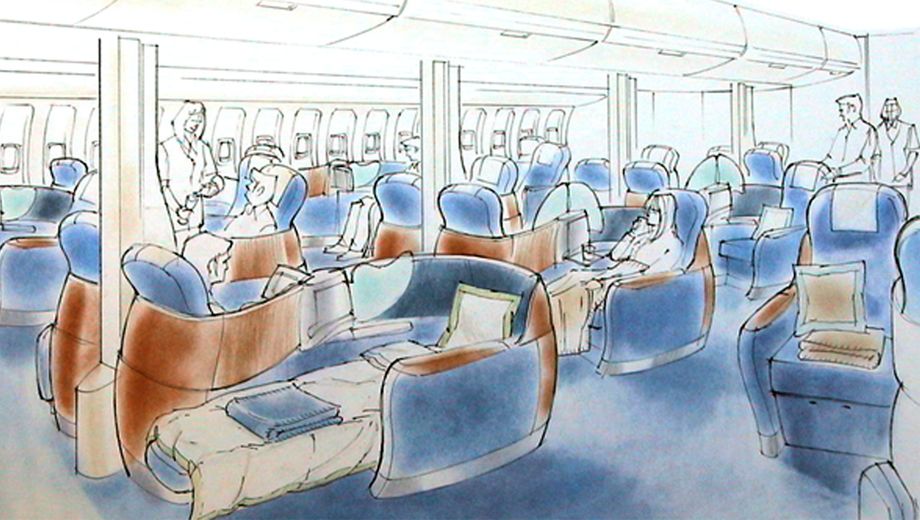

British Airways’ Club World Cradles were arranged seven seats to a row – two seats between window and aisle, three more in the middle, then two more again. And with a limited number of rows in the business class cabin, this shaped an immutable equation: passengers x fare = revenue.

No airline would eagerly reduce its revenue or increase its fares, so Tangerine had to do more than simply astound British Airways. It had to change the maths.

One observation which struck the Tangerine team was that while passengers spent most of their journey in the seat, the aircraft aisles at that time were significantly wider than today.

“Looking at the amount of space dedicated to the aisle versus the amount of space that was dedicated to the seats, we could see there was a lot of aisle space that people spent very little time in,” Round says. “Here was wasted space across the width of the plane that wasn't being capitalised upon.”

This was the first of two pivotal decisions in the evolution of BA’s new Club World seat: changing the distribution of floor space onboard the aircraft, to give overly-generous and under-used aisle space back to passengers.

Tangerine began to think of “using the width of the cabin, not just the length of it, to deliver flat beds.”

But space alone wasn’t the answer.

British Airways had to see a solid business case for lie-flat business class, and that meant not cutting back on passenger capacity in the already seven-across Club World cabin. Bums on seats trumped bums on beds.

Project Dusk

British Airways had codenamed the development of its new business class seat as ‘Project Dusk’. Round believes the moniker was less about having relaxed passengers drifting off to sleep than “because they thought we would be working late on it – and that was a mild understatement!”

Project Midnight or even Project Dawn may have been more apt. BA’s schedule allowed just 18 months from fanciful brief to first flight, and the clock was ticking as Tangerine workshopped the new shape of Club World.

“We did seats facing forward, backwards, sideways, angled, right-angled, seats stacked on top of each other and seats that were separate from beds,” says Round. “We actually explored many of the things that you see today.”

The breakthrough came about during those exercises in seat geometry.

Mulling the tapered shape of the human body – wider at the shoulders, narrower at the feet – Round hit upon a Tetris-like solution.

Seating passengers side by side but facing different directions, one forwards and the other backwards, would interpolate the wider and narrower parts of the body.

This unique and quickly-patented approach was dubbed a yin-yang layout.

“No one had ever considered arranging cabin space in this way,” Round says. More importantly, the maths – and thus the economics – worked.

Round’s groundbreaking yin-yang configuration, combined with stealing space from the aisles, gave British Airways a fully-flat six-foot bed in business class with eight seats per row – an unexpected bonus of one more seat to sell, compared to the seven-across cradle recliners.

As innovative as the yin-yang design was, some passengers were less enthused that they could end up ‘flying backwards’.

“You want people to sit and fly backwards?”

“We built an entire cabin mock-up out of blue foam at BA’s Cabin Development Centre at Heathrow, and brought (BA Executive Club) Gold card holders through to get their reactions about the overall concept,” Round says.

“It was, on the whole, very positive, but a small number of people said, 'If you put seats on planes backwards, I will never ever fly with you again!’"

Round didn’t let the criticism give him pause. “This was more about consumer acceptance than it was about anything real, and you’re always going to get resistance to new ideas. The challenge is, at what speed can you diminish that resistance?”

Tangerine decided to offer a compelling pair of inducements for passengers choosing the backwards-facing seats: the lure of a window plus added privacy during those long flights.

“We placed all the rearward-facing seats next to the window to offset the negatives of flying backwards,” Round elaborates.

The view and privacy “were something that passengers valued very highly, so we were offsetting any potential perceived negatives with positives.”

Frequent flyers’ first reactions

The recollections of London-based architect and frequent BA traveller Gregor Milne, on his first flight in the new Club World seat to Chicago in the early 2000s, bears that out.

“I wanted a window seat but I'd never flown backwards before,” Milne tells Executive Traveller.

“So I was a little bit apprehensive, a little bit curious as to how that would feel, how I would orientate myself and whether I'd notice it or not.”

“Actually there was nothing to worry about at all. It was very comfortable, in fact I was kind of marvelling at the fact that I had three windows all to myself!”

Another Tangerine touch was that the seats were mounted low to the floor and slightly ‘pre-reclined’.

“As soon as I sat down in the (Club World) seat, I just felt very comfortable,” Milne adds.

“I loved the fact that the seat sat very low to the floor. Even in the landing and takeoff mode, there's still a generous amount of recline in the seats and you can really cosy in.”

Snug as a bug in a business class rug

Round smiles at Milne’s recognition of this design aspect. “Something we knew would make (the seat) more comfortable, from work that we do in other industries, was to lower the seat height.”

“It was also more reclined, so instantly you were getting on board and were sat in a more comfortable, more reclined position. And I think if you're comfortable instantly, that then affects your perception of the entire flight, and how comfortable the space is.”

“Beyond just lying down flat, (Project Dusk) was also about privacy,” Round adds. Travellers were no longer likely to be sitting right next to a stranger, even if the yin-yang grid meant they sometimes had to look them in the face.

“We wanted to give people an environment where they could work on documents that might be confidential, where they could feel more like they were nested into their own space, settling down to watch a movie or just having dinner by themselves.”

“And within that private space we were building in flexibility, with the separate seat and footstool, in the way that the people could change their posture and use their space to do different things.”

“People started sitting up on the bed while working on a laptop, or having breakfast in bed. You could shift your legs about much more, put your feet up or down. So it became much more like being in a lounge at home, and this kind of ‘lounge in the sky’ concept was really the thing that was driving the overall experience for the customers.”

Sleep-testing the seat in secret workshops

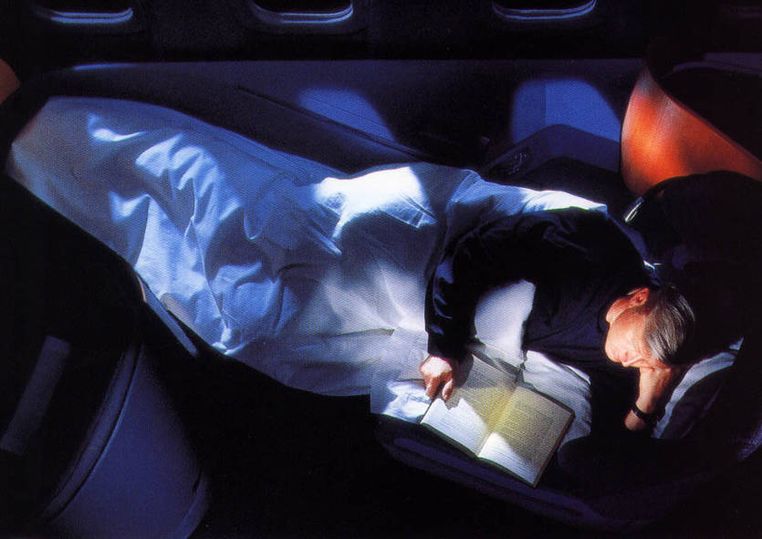

For any lie-flat bed, let alone the first of its kind in business class, sleep would always be the raison d’être.

Scores of volunteers spent the night in mock-ups of the seat so that Tangerine could assess how much ‘sleeping space’ passengers would have.

Low-light video cameras and wrist-strap monitors recorded how people moved as they slept, while a small number of portable seat mock-ups were shipped to the bedrooms of selected passengers and “placed on top of people's beds so that we had a kind of comparative benchmark” of their bed versus the Club World bed, Round says.

British Airways unleashed its fully-flat Club World seats on the prestigious trans-Atlantic route between London and New York in March 2000, with Boeing 747 jumbo jets each carrying 96 business class passengers.

David Jagoe, a senior audit manager in London’s banking sector, recalls first flying in the new Club World seat in 2001 on a trip from Vancouver.

“It was such a massive jump from the cradle seats, a groundbreaking experience,” Jagoe tells Executive Traveller.

“The old business class seats of those days, the cradles, reclined a lot – but you were reclining into someone else, and someone else was reclining into you. People bumped you, or you felt trapped. Suddenly all those problems seemed taken away.”

British Airways’ passenger-packing layout would many years later be considered a major shortcoming as other airlines rolled out roomier six-across and then four-across seating with direct aisle access.

But Tangerine says the sheer number of business class passengers on each aircraft delivered BA a return on its investment in the new Club World seat “within 12 months” and later trumpeted the new business class as the airline’s “profit engine”.

“Launching a new business class seat involves the spend of several hundred million pounds, it’s a big investment,” posits Martin Darbyshire, co-founder and CEO of Tangerine. “But if you get it right, as we have done, the returns are massive in comparison.”

Club World 2.0

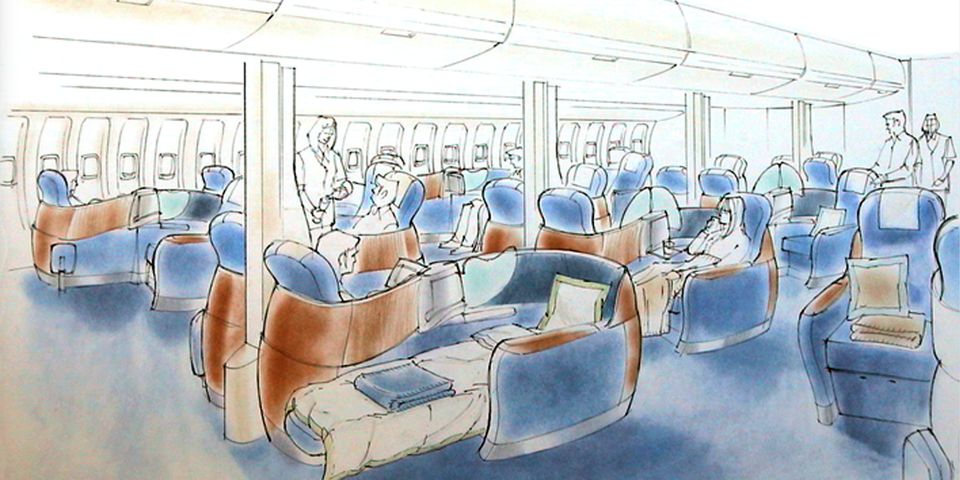

Four years later, Tangerine was called upon to give the Club World seat a comprehensive ‘Version 2.0’ make-over.

British Airways was determined to stay ahead in an increasingly-competitive game, against heavyweights such as Singapore Airlines and hungry challengers like Virgin Atlantic.

“There were a lot of things that weren't right with the first version,” Round admits. “It was a kind of point of getting to market very quickly (because) the project happened in less than 18 months.”

The next generation Club World flatbed seat, revealed to the media at London’s Canary Wharf in November 2006, retained the core flat-bed concept, footstool and yin-yang pattern – but with everything else redesigned, re-engineered and wrapped in a then-contemporary flat silver shell. It’s the same international business class seat which British Airways still flies today.

The bed gained an extra 25% in width and also became longer – stretching to the same 6’6” (2m) as the beds in first class – with armrests that lowered as the seat reclined, to unlock even more lateral space when sleeping.

Tangerine revamped the seat recline, base and footstool to introduce a relaxing ‘lazy Z’ position with support for the knees and back.

An immediate casualty was the concertina fan which served as a privacy screen between adjacent seats.

“The fan was not something that we were all very fond of,” Round shares. “There were lots and lots of other solutions, but the fan was the only thing that actually met all of the criteria that were laid down.”

Foremost was an essential safety regulation surround deployment of the overhead oxygen masks: the fan made it possible for a passenger “to reach through from their side to get the oxygen mask if it had fallen on the other side of the fan,” Round explains, “without lifting their shoulders from their flat-bed.”

“That privacy screen was obviously one of the targets” in the 2006 Club World seat, Round says. A translucent frosted panel replaced the fan, with a sensor linked to the same circuitry as the oxygen masks.

When the masks are activated, "the solenoid holding up the privacy screen loses its power, so the privacy screen itself drops, and you can then reach through to get the oxygen mask.”

But yes, it’s loud. “That's the bit that gets me the most, the noise it makes” laughs architect Gregor Milne.

“When you're in a window seat, you're in your own little world, and then from out of nowhere there’s a buzzsaw burst with a face peering at you through the screen. It can be quite startling.”

While British Airways has since moved to an all-new Club Suites in business class, Tangerine’s Round rightly considers the Club World design of 2000 as “one of the most innovative things the aviation industry has ever done.”

“If you reflect that the concept has been flying for almost two decades, it’s evidence that it was a very strong design that stood the test of time.”

“Now the market has changed a lot, and BA is moving on – but I think the Club World product shows that you can get real innovation if you really explore the problem, use design wisely and create the right environment for innovation to happen.”