In the ultra-long haul, 'hub' airports may be left behind

Singapore Airlines' decision to restart direct flights to New York is a boon to the city-state's standing as a global aviation hub. It’s also an ominous sign for the future of such centers.

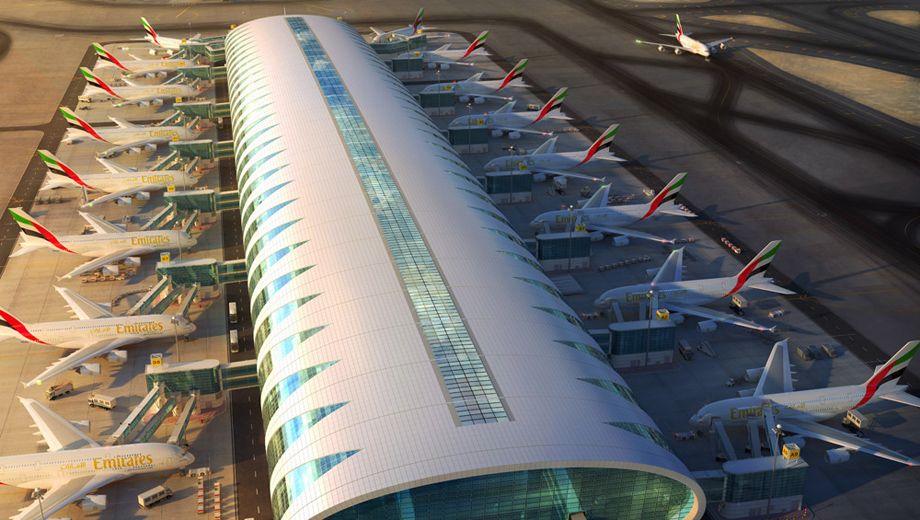

Singapore, Hong Kong, Los Angeles and Dubai became hubs from the 1970s to the 2000s for a simple reason: commercial aircraft of the era struggled to travel more than about 10,000 kilometers without stopping to refuel.

That put swathes of the Americas off-limits to direct flights from East Asia, and meant travelers between Europe and Australia had to touch down in the Gulf or Asia en route. You can get a rough sense of the limitations by playing with this interactive map provided by Airbus.

While low oil prices in the 1990s and early 2000s inspired a few attempts to venture further afield, fuel-hungry designs checked the industry’s enthusiasm.

The Airbus A340-500, introduced in 2002 just as oil was starting its climb to US$148 a barrel, carries nearly as much kerosene as a 747. Boeing’s longest-range jet, the 777-200LR, has won just 59 orders since its maiden flight in 2005.

Technology is finally catching up. Fuel typically makes up about a quarter of an airline’s operating costs, and Boeing’s 787 and Airbus’s A350 have squeezed every ounce of benefit out of advanced materials and improved engine designs to use less.

That may mean geography isn’t destiny the way it was in the past. Southeast Asian airlines including Singapore Airlines, Malaysia Airlines and Thai Airways will be able to compete with Cathay Pacific and Emirates on North American routes, according to Capa Centre for Aviation, a consultancy.

Being jammed into a pressurized tube for 19 hours at a time isn’t everyone’s idea of fun. Still, time-conscious executives whose companies are paying for lie-flat beds seem to love it.

Singapore Airlines' previous direct New York route, killed off in 2013 in the face of high oil prices, carried just 100 passengers in an all-business-class A340-500.

Business-class tickets bring in about 3.6 times more revenue per passenger, per kilometer than economy ones and so make up a disproportionate share of airline profits. Catering to more passengers at the front of the plane helps airlines keep prices competitive at the back.

The likes of Singapore and Dubai will still have a role. Hubs allow airlines to serve a greater variety of destinations with fewer planes, as in the U.S. domestic market. Qantas added 25 European destinations to a previous tally of five by striking an alliance with Emirates in 2012.

But if business class passengers start migrating to the ultra-long-haul routes being opened up by Boeing and Airbus' new designs, the hubs risk becoming conduits for lower-margin mass traffic.

31 Mar 2016

Total posts 619

21 Apr 2012

Total posts 3006

KUL, DXB, AUD, DOH and to a lesser extent, BKK are hub airports for their respective home carriers. In my mind this does not make them truly hubs, in that they merely facilitate their home carrier's business model, and not a focal point for the convergence of a free market.

In addition to being hubs, cities need to be destinations in their own right to enable their airports and home carriers to thrive. In that I believe CX/HKG and SQ/SIN will continue to be significant players, once they sort out their marketing mix and product/service.

Qantas - Qantas Frequent Flyer

15 Mar 2016

Total posts 167

Spot on. DXB, AUH and DOH especially would, and previously did, see almost no traffic. Their almost sole purpose is as a conduit for traffic from one part of the world to another - they don't have and arguably won't ever have the appeal as a destination in their own right as the Asian 'hubs'.

QF

04 Apr 2014

Total posts 210

Spot on. There are reasons to go to places like Singapore and Los Angeles irrespective of flight routes.

20 May 2015

Total posts 579

"But if business class passengers start migrating to the ultra-long-haul routes being opened up by Boeing and Airbus' new designs, the hubs risk becoming conduits for lower-margin mass traffic."

That's exactly what will happen.

The logical implication is that we'll have volume-based megahub airlines carrying most low-margin traffic in economy-heavy configurations on one hand, and yield-driven point-to-point airlines carrying more high-margin traffic in less dense configurations on the other. Emirates, Etihad, Singapore Airlines etc.. The premium product they fly (on any particular route) will eventually be equivalent to the amount of premium demand between their hub and the destination city in question.

Hi Guest, join in the discussion on In the ultra-long haul, 'hub' airports may be left behind